Spiritual Ground of Education

GA 305

V. How Knowledge Can Be Nurture

21 August 1922, Oxford

If the process of the change of teeth in a child is gradual even more gradual is that great transformation in the bodily, psychic and spiritual organism of which I have already spoken. Hence, in education it is important to remember that the child is gradually changing from an imitative being into one who looks to the authority of an educator, of a teacher. Thus we should make no abrupt transition in the treatment of a child in its seventh year or so—at the age, that is, at which we receive it for education in the primary school. Anything further that is said here on primary school education must be understood in the light of this proviso.

In the art of education with which we are here concerned the main thing is to foster the development of the child's inherent capacities. Hence all instruction must be at the service of education. The task is, properly speaking, to educate; and instruction is made use of as a means of educating.

This educational principle demands that the child shall develop the appropriate relation to life at the appropriate age. But this can only be done satisfactorily when the child is not required at the very outset to do something which is foreign to its nature.

Now it is a thoroughly unnatural thing to require a child in its sixth or seventh year to copy without more ado the signs which we now, in this advanced stage of civilisation, use for reading and writing.

If you consider the letters we now use for reading and writing, you will realise that there is no connection between what a seven-year old child is naturally disposed to do—and these letters. Remember, that when men first began to write they used painted or drawn signs which copied things or happenings in the surrounding world; or else men wrote from out of will impulses, so that the forms of writing gave expression to processes of the will, as for example in cuneiform. The entirely abstract forms of letters which the eye must gaze at nowadays, or the hand form, arose from out of picture writing. If we confront a young child with these letters we are bringing to him an alien thing, a thing which in no wise conforms to his nature. Let us be clear what this ‘pushing’ of a foreign body into a child's organism really means. It is just as if we habituated the child from his earliest years to wearing very small clothes, which do not fit and which therefore damage his organism. Nowadays when observation tends to be superficial, people do not even perceive what damage is done to the organism by the mere fact of introducing reading and writing to the child in a wrong way. An art of education founded in a knowledge of man does truly proceed by drawing out all that is in the child. It does not merely say: the individuality must be developed, it really does it. And this is achieved firstly by not taking reading as the starting point. For with a child the first things are movements, gestures, expressions of will, not perception or observation. These come later. Hence it is necessary to begin, not with reading, but with writing—but a writing which shall come naturally from man's whole being.

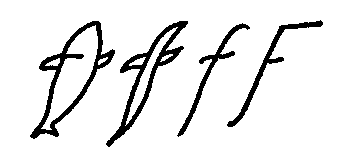

Hence, we begin with writing lessons, not reading lessons, and we endeavour to lead over what the child does of its own accord out of imitation, through its will, through its hands, into writing. Let me make it clear to you by an example: We ask the child to say the word “fish,” for instance, and while doing so, show him the form of the fish in a simple sketch; then ask him to copy it;—thus we get the child to experience the word “fish.” From “fish” we pass to f (F), and from the form of the fish we can gradually evolve the letter f. Thus we derive the form of the letter by an artistic activity which carries over what is observed into what is willed:

By this means we avoid introducing an utterly alien F, a thing which would affect the child like a demon, something foreign thrust into his body; and instead we call forth from him the thing he has seen himself in the market place. And this we transform little by little into ‘ f .’

In this way we come near to the way writing originated, for it arose in a manner similar to this. But there is no need for the teacher to make a study of antiquity and exactly reproduce the way picture writing arose so as to give it in the same manner to the child. What is necessary is to give the rein to living fantasy and to produce afresh whatever can lead over from the object, from immediate life, to the letter forms. You will then find the most manifold ways of deriving the letter form for the child from life itself. While you say M let him feel how the M vibrates on the lips, then get him to see the shape of the lips as form, then you will be able to pass over gradually from the M that vibrates on the lips to M.

In this way, if you proceed spiritually, imaginatively, and not intellectually, you will gradually be able to derive from the child's own activity, all that leads to his learning to write. He will learn to write later and more slowly than children commonly do to-day. But when parents come and say: My child is eight, or nine years old, and cannot yet write properly, we must always answer: What is learned more slowly at any given age is more surely and healthily absorbed by the organism, than what is crammed into it.

Along these lines, moreover, there is scope for the individuality of the teacher, and this is an important con-sideration. As we now have many children in the Waldorf School we have had to start parallel classes—thus we have two first classes, two second classes and so on. If you go into one of the first classes you will find writing being taught by way of painting and drawing. You observe how the teacher is doing it. For instance, it might be just as we have been describing here. Then you go into the other Class I., Class I. B; and you find another teacher teaching the same subject. But you see something quite different. You find the teacher letting the children run round in a kind of eurhythmy, and getting them to experience the form from out of their own bodily movements. Then what the child runs is retained as the form of the letter. And it is possible to do it in yet a third and a fourth manner. You will find the same subject taught in the most varied ways in the different parallel classes. Why? Well, because it is not a matter of indifference whether the teacher who has to take a lesson has one temperament or another. The lesson can only be harmonious when there is the right contact between the teacher and the whole class. Hence every teacher must give his lesson in his own way. And just as life appears in manifold variety so can a teaching founded in life take the most varied forms.

Usually, when pedagogic principles are laid down it is expected that they shall be carried out. They are written down in a book. The good teacher is he who carries them out punctiliously, 1, 2, 3, etc. Now I am convinced that if a dozen men, or even fewer, sit down together they can produce the most wonderful programme for what should take place in education; firstly, secondly, thirdly, etc. People are so wonderfully intelligent nowadays;—I am not being sarcastic, I really mean it—one can think out the most splendid things in the abstract. But whether it is possible to put into practice what one has thought out is quite another matter. That is a concern of Life. And when we have to deal with life,—I ask you now, life is in all of you, natural life, you are all human beings, yet you all look different. No one man's hair is like another's. Life displays its variety in the manifold varieties of form. Each man has a different face. If you lay down abstract principles, you expect to find the same thing done in every class room. If your principles are taken from life, you know that life is various, and that the same thing can be done in the most varied ways. You see, for instance, that Negroes must be regarded as human beings, and in them the human form appears quite differently. In the same way when the art of education is held as a living art, all pedantry and also every kind of formalism must be avoided. And education will be true when it is really made into an art, and when the teacher is made into an artist. It is thus possible for us in the Waldorf School to teach writing by means of art. Then reading can be learned afterwards almost as a matter of course, without effort. It comes rather later than is customary, but it comes almost of itself.

While we are concerned on the one hand in bringing the pictorial element to the child—(and during the next few days I shall be showing you something of the paintings of the Waldorf School children)—while we are engaged with the pictorial element, we must also see to it that the musical element is appreciated as early as possible. For the musical element will give a good foundation for a strong energetic will, especially when attention is paid—at this stage—not so much to musical content as to the rhythm and beat of the music, the experience of rhythm and beat; and especially when it is treated in the right manner at the beginning of the elementary school period. I have already said in the introduction to the eurhythmy demonstration that we also introduce eurhythmy into children's education. I shall be speaking further of eurhythmy, and in particular of eurhythmy in education, in a later lecture. For the moment I wished to show more by one or two examples how early instruction serves the purpose of education in so far as it is called out of the nature of the human being.

But we must bear in mind that in the first part of the stage between the change of teeth and puberty a child can by no means distinguish between what is inwardly human and what is external nature. For him up to his eighth or ninth year these two things are still merged into one. Inwardly the child feels a certain impression, outwardly he may see a certain phenomenon, for instance a sunrise. The forces he feels in himself when he suffers unhappiness or pain; he supposes to be in sun or moon, in tree or plant. We should not reason the child out of this. We must transpose ourselves into the child's stage of life and conduct everything within education as if no boundary existed as yet between inner man and outer nature. This we can only do when we form the instruction as imaginatively as possible, when we let the plants act in a human manner—converse with other plants, and so on,—when we introduce humanity everywhere. People have a horror nowadays of Anthropomorphism, as it is called. But the child who has not experienced anthropomorphism in its relation to the world will be lacking in humanity in later years. And the teacher must be willing to enter into his environment with his full spirit and soul so that the child can go along with him on the strength of this living experience.

Now all this implies that a great deal shall have happened to the teacher before he enters the classroom. The carrying through of the educational principles of which we have been speaking makes great demands on the preparation the teachers have to do. One must do as much as one possibly can before-hand when one is a teacher, in order to make the best use of the time in the class room. This is a thing which the teacher learns to do only gradually, and in course of time. And only through this slow and gradual learning can one come really to have a true regard for the child's individuality.

May I mention a personal experience in this connection, Years before my connection with the Waldorf School I had to concern myself with many different forms of education. Thus it happened that when I was still young myself I had corded to me the education of a boy of eleven years old who was exceedingly backward in his development. Up to that time he had lied nothing at all. In proof of his attainment I was shown an exercise book containing the results of the latest examination he had been pushed into. All that was to be seen in it was an enormous hole that he had scrubbed with the india-rubber; nothing else. Added to this the boy's domestic habits were of a pathological nature. The whole family was unhappy on his account, for they could not bring themselves to abandon him to a manual occupation—a social prejudice, if you like, but these prejudices have to be reckoned with. So the whole family was unhappy. The family doctor was quite explicit that nothing could be made of the boy. I was now given four children of this family to educate. The others were normal, and I was to educate this one along with them. I said: I will try—in a case like this one can make no promises that this or the other result will be achieved,—but I would do everything that lay within my power, only I must be left complete freedom in the matter of the education. So now I undertook this education. The mother was the only member of the family who understood my stipulation for freedom, so that the education had to be fought for him in the teeth of the others. But finally the instruction of the boy was confided to me. It was necessary that the time spent in immediate instruction of the boy should be as brief as possible. Thus if I had, say, to be engaged in teaching the boy for about half-an-hour, I had to do three hours' work in preparation so as to make the most economical use of the time. Moreover, I had to make careful note of the time of the music lesson, for example. For if the boy were overtaxed he turned pale and his health deteriorated. But because one understood the boy's whole pathological condition, because one knew what was to be set down to hydrocephalus, it was possible to make such progress with the boy—and not psychical progress only,—that a year and a half after he had shown up merely a hole rubbed in his exercise book, he was able to enter the Gymnasium. (Name given to the Scientific and Technical School as distinct from the Classical.) And I was further able to help him throughout the classes of the Gymnasium and follow up the work with him until near the end of his time there, Under the influence of this education, and also because everything was spiritually directed, the boy's head became smaller. I know a doctor might say perhaps his head would have become smaller in any case. Certainly, but the right nurture of spirit and soul had to go with this process of getting smaller. The person referred to subsequently became an excellent doctor. He died during the war in the exercise of his profession, but only when he was nearly forty years old.

It was particularly important here to achieve the greatest economy in the time of instruction by means of suitable preparation beforehand. Now this must become a general principle. And in the art of education of which I am here speaking this is striven for. Now, when it is a question of describing what we have to tell the children in such a way as to arouse life and liveliness in their whole being, we mast master the subject thoroughly beforehand and be so at home with the matter that we can turn all our attention and individual power to the form in which we shall present it to the child. And then we shall discover as a matter of course that all the stuff of teaching must become pictorial if a child is to grasp it not only with his intellect but with his whole being. Hence we mostly begin with tales such as fairy tales, but also with other invented stories which relate to Nature. We do not at first teach either language or any other “subject,” but we simply unfold the world itself in vivid and pictorial form before the child. And such instruction is the best preparation for the writing and reading which is to be derived imaginatively.

Thus between his ninth and tenth year the child comes to be able to express himself in writing, and also to read as far as is healthy for him at this age, and now we have reached that important point in a child's life, between his ninth and tenth year, to which I have already referred. Now you must realise that this important point in the child's life has also an outward manifestation. At this time quite a remarkable change takes place, a remarkable differentiation, between girls and boys. Of the particular significance of this in a co-educational school such as the Waldorf School, I shall be speaking later. In the meantime we must be aware that such a differentiation between boys and girls does take place. Thus, round about the tenth year girls begin to grow at a quicker rate than the boys. Growth in boys is held back. Girls overtake the boys in growth. When the boys and girls reach puberty the boys once more catch up with the girls in their growth. Thus just at that stage the boys grow more rapidly.

Between the tenth and fifteenth year the outward differentiation between girls and boys is in itself a sign that a significant period of life has been reached. What appears inwardly is the clear distinction between oneself and the world. Before this time there was no such thing as a plant, only a green thing with red flowers in which there is a little spirit just as there is a little spirit in ourselves. As for a “plant,” such a thing only makes sense for a child about its tenth year. And here we must be able to follow his feeling. Thus, only when a child reaches this age is it right to teach him of an external world of our surroundings.

One can make a beginning for instance with botany—that great stand-by of schools. But it is just in the case of botany that I can demonstrate how a formal education—in the best sense of the word—should be conducted. If we start by showing a child a single plant we do a thoroughly unnatural thing, for that is not a whole. A plant especially when it is rooted up, is not a whole thing. In our realistic and materialistic age people have little sense for what is material and natural otherwise they would feel what I have just said. Is a plant a whole thing? No, when we have pulled it up and fetched it here it very soon withers. It is not natural to it to be pulled up. Its nature is to be in the earth, to belong with the soil. A stone is a totality by itself. It can lie about anywhere and it makes no difference. But I cannot carry a plant about all over the place; it will not remain the same. Its nature is only complete in conjunction with the soil, with the forces that spring from the earth, and with all the forces of the sun which fall upon this particular portion of the earth. Together with these the plant makes a totality. To look upon a plant in isolation is as absurd as if we were to pull out a hair of our head and regard the hair as a thing in itself. The hair only arises in connection with an organism and cannot be understood apart from the organism. Therefore: In the teaching of botany we must take our start, not from the plant, or the plant family but from the landscape, the geographical region: from an understanding of what the earth is in a particular place. And the nature of plants must be treated in relation to the whole earth.

When we speak of the earth we speak as physicists, or at most as geologists. We assume that the earth is a totality of physical forces, mineral forces, self-enclosed, and that it could exist equally well if there were no plants at all upon it, no animals at all, no men at all. But this is an abstraction. The earth as viewed by the physicist, by the geologist, is an abstraction. There is in reality no such thing. In reality there is only the earth which is covered with plants. We must be aware when we are describing from a geological aspect that, purely for the convenience of our intelligence, we are describing a non-existent abstraction. But we must not start by giving a child an idea of this non-existent abstraction, we must give the child a realisation of the earth as a living organism, beginning naturally with the district which the child knows. And then, just as we should show him an animal with hair growing upon it, and not produce a hair for it to see before it knew anything of the animal—so must we first give him a vivid realisation of the earth as a living organism and after that show him how plants live and grow upon the earth.

Thus the study of plants arises naturally from introducing the earth to the child as a living thing, as an organism—beginning with a particular region. To consider one part of the earth at a time, however, is an abstraction, for no region of the earth can exist apart from the other regions; and we should be conscious that we take our start from something incomplete. Nevertheless, if, once more we teach pictorially and appeal to the wholeness of the imagination the child will be alive to what we tell him about the plants. And in this way we gradually introduce him to the external world. The child acquires a sense of the concept “objectivity.” He begins to live into reality. And this we achieve by introducing the child in this natural manner to the plant kingdom.

The introduction to the animal kingdom is entirely different—it comes somewhat later. Once more, to describe the single animals is quite inorganic. For actually one could almost say: It is sheer chance that a lion is a lion and a camel a camel. A lion presented to a child's contemplation will seem an arbitrary object however well it may be described, or even if it is seen in a menagerie. So will a camel. Observation alone makes no sense in the domain of life.

How are we to regard the animals? Now, anyone who can contemplate the animals with imaginative vision, instead of with the abstract intellect, will find each animal to be a portion of the human being. In one animal the development of the legs will predominate—whereas in man they are at the service of the whole organism. In another animal the sense organs, or one particular sense organ, is developed in an extreme manner. One animal will be specially adapted for snouting and routing (snuffling), another creature is specially gifted for seeing, when aloft in the air. And when we take the whole animal kingdom together we find that what outwardly constitutes the abstract divisions of the animal kingdom is comprised in its totality in man. All the animals taken together, synthetically, give one the human being. Each capacity or group of faculties in the human being is expressed in a one-sided form in some animal species. When we study the lion—there is no need to explain this to the child, we can show it to him in simple pictures—when we study the lion we find in the lion a particular over-development of what in the human being are the chest organs, the heart organ. The cow shows a one-sided development of what in man is the digestive system. And when I examine the white corpuscles in the human blood I see the indication of the earliest, most primitive creatures. The whole animal kingdom together makes up man, synthetically, not symptomatically, but synthetically woven and interwoven.

All this I can expound to the child in quite a simple, primitive way. Indeed I can make the thing very vivid when speaking, for instance, of the lion's nature and showing how it needs to be calmed and subdued by the individuality of man. Or one can take the moral and psychic characteristics of the camel and show how what the camel presents in a lower form is to be found in human nature. So that man is a synthesis of lion, eagle, ape, of camel, cow and all the rest. We view the whole animal kingdom as human nature separated out and spread abroad.

This, then, is the other side which the child gets when he is in his eleventh or twelfth year. After he has learned to separate himself from the plant world, to experience its objectivity and its connection with an objective earth, he then learns the close connection between the animals and man, the subjective side. Thus the universe is once more brought into connection with man, by way of the feelings. And this is educating the child by contact with life in the world.

Then we shall find that the requirements we always make are met spontaneously. In theory we can keep on saying: You must not overload the memory. It is not a good thing to burden the child's memory. Anyone can see that in the abstract. It is less easy for people to see clearly what effect the overburdening of memory has on a man's life. It means this, that later in life we shall find him suffering from rheumatism and gout—it is a pity that medical observation does not cover the whole span of a man's life, but indeed we shall find many people afflicted with rheumatism and gout, to which they had no predisposition; or else what was a very slight predisposition has been in-creased because the memory was overtaxed, because one had learned too much from memory. But, on the other hand, the memory must not be neglected. For if the memory is not exercised enough inflammatory conditions of the physical organs will be prone to arise, more particularly between the 16th and 24th years.

And how are we to hold the balance between burdening the memory too much or too little? When we teach pictorially and imaginatively, as I have described, the child takes as much of the instruction as it can bear. A relationship arises like that between eating and being satisfied. This means that we shall have some children further advanced than others, and this we must deal with, without relegating less advanced children to a class below. One may have a comparatively large class and yet a child will not eat more than it can bear—spiritually speaking—because its organism spontaneously rejects what it cannot bear. Thus we take account of life here, just as we draw our teaching from life.

A child is able to take in the elements of Arithmetic at quite an early age. But in arithmetic we observe how very easily an intellectual element can be given the child too soon. Mathematics as such is alien to no man at any age. It arises in human nature; the operations of mathematics are not foreign to human faculty in the way letters are foreign in a succeeding civilisation. But it is exceedingly important that the child should be introduced to arithmetic and mathematics in the right way. And what this is can really only be decided by one who is enabled to overlook the whole of human life from a certain spiritual standpoint.

There are two things which in logic seem very far removed from one another: arithmetic and moral principles. It is not usual to hitch arithmetic on to moral principles because there seems no obvious logical connection between them. But it is apparent to one who looks at the matter, not logically, but livingly, that the child who has a right introduction to arithmetic will have quite a different feeling of moral responsibility from the child who has not. And—this may seem extremely paradoxical to you, but since I am speaking of realities and not of the illusions current in our age, I will not be afraid of seeming paradoxical, for in this age truth often seems paradoxical.—If, then, men had known how to permeate the soul with mathematics in the right way during these past years we should not now have bolshevism in Eastern Europe. This it is that one perceives: what forces connect the faculty used in arithmetic with the springs of morality in man.

Now, you will understand this better probably if I give you a very small illustration of the principles of arithmetic teaching. It is common nowadays to start arithmetic by the adding of one thing to another. But just consider how foreign a thing it is to the human mind to add one pea to another and at each addition to name a new name. The transition from one to two, and then to three,—this counting is quite an arbitrary activity for the human being. But it is possible to count in another way. And this we find when we go back a little in human history. For originally people did not count by putting one pea to another and hence deriving a new thing which, for the soul at all events, had little connection with what went before. No, men counted more or less in the following way: They would say: What we get in life is always a whole, something to be grasped as a whole; and the most diverse things can constitute a unity. If I have a number of people in front of me, that can be a unity at first sight. Or if I have a single man in front of me, he then is a unity. A unity, in reality, is a purely relative thing. And I keep this in mind if I count in the following way: One | = | two | = | = | three | = | = | = | four | = | = | =| = | and so on, that is, when I have an organic whole (a whole consisting of members): because then I am starting with unity, and in the unity, viewed as a multiplicity, I seek the parts. This indeed was the original view of number. Unity was always a totality, and in the totality one sought for the parts. One did not think of numbers as arising by the addition of one and one and one, one conceived of the numbers as belonging to the whole, and proceeding organically from the whole.

When we apply this to the teaching of arithmetic we get the following: Instead of placing one bean after another beside the child, we throw him a whole heap of beans. The bean heap constitutes the whole. And from this we make our start. And now we can explain to the child: I have a heap of beans—or if you like, so that it may the better appeal to the child's imagination: a heap of apples,—and three children of different ages who need different amounts to eat, and we want to do something which applies to actual life. What shall we do? Now we can for instance, divide the heap of apples in such a way as to give a certain heap on the one hand and portions, together equal to the first heap, on the other. The heap represents the sum. Here we have the heap of apples, and we say: Here are three parts, and we get the child to see that the sum is the same as the three parts. The sum = the three parts. That is to say, in addition we do not go from the parts to arrive at the sum, but we start with the sum and proceed to the parts. Thus to get a living understanding of addition we start with the whole and proceed to the addenda, to the parts. For addition is concerned essentially with the sum and its parts, the members which are contained, in one way or another, within the sum.

In this way we get the child to enter into life with the ability to grasp a whole, not always to proceed from the less to the greater. And this has an extraordinarily strong influence upon the child's whole soul and mind. When a child has acquired the habit of adding things together we get a disposition which tends to be desirous and craving. In proceeding from the whole to the parts, and in treating multiplication similarly, the child has less tendency to acquisitiveness, rather it tends to develop what, in the Platonic sense, the noblest sense of the word, can be called considerateness, moderation. And one's moral likes and dislikes are intimately bound up with the manner in which one has learned to deal with number. At first sight there seems to be no logical connection between the treatment of numbers and moral ideas, so little indeed that one who will only regard things from the intellectual point of view, may well laugh at the idea of any connection. It may seem to him absurd. We can also well understand that people may laugh at the idea of proceeding in addition from the sum instead of from the parts. But when one sees the true connections in life one knows that things which are logic-ally most remote are often in reality exceedingly near.

Thus what comes to pass in the child's soul by working with numbers will very greatly affect the way he will meet us when we want to give him moral examples, deeds and actions for his liking or disliking, sympathy with the good, antipathy with the evil. We shall have before us a child susceptible to goodness when we have dealt with him in the teaching of numbers in the way described.