Health and Illness I

GA 348

VI. The Nose, Smell, and Taste

16 December 1922, Dornach

As you recall, gentlemen, last time we talked about the eye, and we were particularly impressed with its marvellous configuration. Even in regard to its external form, the eye reproduces a whole world. When we become acquainted with the interior of the eye, the way we did the last time, we discover that there is indeed a miniature world within. That I have explained to you, and thus we have become familiar with two senses of man, sight and hearing.

Now, in connection with other questions you have recently posed, we shall see that a particularly fascinating and interesting human sense is that of smell. This sense appears to be of minor importance in man but, as you know, it is of great significance in the dog. You could say that all the intelligence of the dog is, in fact, transferred to the sense of smell. You need only consider how much the animal can accomplish by smell. A dog recognizes people by smell long after it has been with them. Anyone who observes dogs knows that they recognize and identify somebody with whom they have been acquainted, not by the sense of sight, but by that of smell. If you have heard recently how dogs can become excellent detectives and search for lawbreakers or for people in general, you will say to yourselves that here the sense of smell accomplishes rare things that naturally appear simple but are in actuality not so simple at all. You need only consider these matters to realize that they are not so simple.

“Well,” you may say casually, “the dog merely follows the scent.” Yes, gentlemen, that is true, the dog does indeed follow the scent. But think about it. Police dogs are used to follow, say, first the track of thief X and then the track of thief Y, one right after the other. The two scents are completely different from each other; if they were alike the dog could naturally never be able to follow them. Imagine now that you had to point out the difference between these tracks that the dogs distinguish by smell; you would discover no significant difference. The dog, however, does detect differences. The point is not that the dog follows the tracks back and forth in general but that it is capable of distinguishing between the various traces of scent. That, indeed, indicates intelligence.

There is yet another extremely important consideration. Civilized men use their sense of smell for foods and other external things, but it doesn't inform them of much else. In contrast, primitive tribes in Africa can smell out their enemies at far range, just as a dog can detect a scent. They are warned of their foes by smell. Thus, the intelligence that is found in such great measure in the dog is also found to a certain degree among primitive people. The member of a primitive tribe in Africa can tell long before he has seen his adversary that he is approaching; he distinguishes him from other people with his nose. Imagine how delicate one's sense of discernment in the nose must be if by that one can know that an enemy is nearby. Also, Africans know how to utter a certain warning sound that Europeans cannot make at all. It is a clicking sound, somewhat like the cracking of a whip.

It can be said that the more civilized a man becomes, the more diminished is the importance of his sense of smell. We can use this sense to ascertain whether we are dealing with a less developed species like the canine family—and they are a lower species—or one more developed. If we were to follow up on this, we would probably make some priceless discoveries about hogs, which, of course, have an exceptionally strong sense of smell.

There is something else in regard to this that will interest you. The elephant is reputed to be one of the most intelligent animals, and it certainly is; the elephant is a highly intelligent animal. Well, what feature is particularly well-developed in the elephant? Look at the area above the teeth in the dog and the pig, the area that in man forms itself into the nose. When you picture an especially strong and pronounced development of this part, you arrive at the elephant's trunk. The elephant possesses what is nose in us to a particularly pronounced degree, and therefore it is the most intelligent animal. The extreme intelligence of the elephant does not depend on the size of the brain but on its extension straight into the nose.

All these facts challenge us to ask how matters stand in respect to the human nose, an organ that civilized man today does not really know too much about. Of course, he is familiar with its anatomy and structure, but basically, he does not know much more than the fact that it sits in the middle of his face. Yet, the nose, with its continuation into the brain, is actually a most interesting organ. If you will recall my descriptions of the ear and the eye, you will say to yourselves that they are complicated. The nose, however, is not so complicated, but it is quite ingenious.

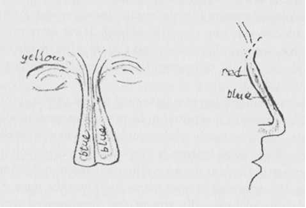

Seen from the front, the nose has a wall in the middle, the septum. This can be felt when you hold your nose. The septum divides the nose into a left and a right side, and to the left and the right are the actual parts of this organ. From the front it looks like this (sketching). The cribriform plate is located in the skull bone up where the nose sits between the eyes. It is like a little sieve. In other words, it is a bone with many holes. It is intricate but in my drawing I shall simplify it. On the exterior, the nose has skin like the skin on the rest of the body; inside, it is completely lined and filled out with a mucous membrane. This is everywhere in the nose, a fact that you can readily confirm. This membrane secretes mucus; if you did not have it, you would not have to blow your nose. So, inside the nose is a membrane that secretes mucus, but the matter is more complicated. You will have noticed that children who cry secrete a lot of nasal mucus. A canal in the upper part of the nose leads to the tear glands, which are located on both sides in the interior. There the secretion, the tears, enters the nose and mixes with the nasal mucus. Thus, the nose has a kind of “fluidic connection” with the eyes. The secretion of the eyes flows into the mucous membrane and combines with the secretion of the nose. This connection shows us again that no organ in the body is isolated. The eyes are not only for seeing; they can also cry, and what they then discharge mixes with what is primarily secreted in the membrane of the nose.

The olfactory nerve, the actual nerve used for smelling, passes through the cribriform plate, which is located at the roof of the nose. This nerve has two fibres that pass from the brain through the sieve-like bone and spread out within the nose. The mucous membrane, which we can touch with our finger, is interlaced by the olfactory nerve, which reaches into the brain. We can easily discern that because the nose is constructed quite simply.

Now we come to something that can reveal much to one who thinks sensibly. You see, a thorough examination will show that no one has eyes of equally strong vision, and when we examine the two hands we readily discover that they are not of equal strength. The organs of the human being are never completely equal in strength on both the left and right side. So it is also with the nose. Generally, we simply do not smell as well with the left nostril as with the right, but it is the same here as it is with the hand; some individuals are better at smelling with the left nostril than with the right, just as some people are left-handed. As you know, some people in the world are screwed together the wrong way. I am not referring to those people whose heads are screwed on wrong [(A play on words. In German, a “Querkopf' is a person who is odd. Rudolf Steiner then uses the term “Querherz” to indicate the anatomical oddity of the heart.)] but to those whose hearts are screwed on the wrong way. In the average person, the heart is located slightly off-centre to the left, as are the rest of the internal organs. Now, in a person whose heart is screwed on the wrong way, as it were, whose heart is off-centre a bit to the right, the stomach is also pushed over slightly to the right. Such a person is all “screwed up,” but this phenomenon is indeed less noticeable than when one is screwed up in the head. The fact becomes apparent when a person has fallen ill or has been dissected. Autopsies first led to the discovery that there are such odd people whose hearts and stomachs are shifted to the right. Of course, since not everyone who is queer in the head is dissected after death, one often doesn't even know that there are many more such “odd people” than is normally assumed whose hearts are off-centre to the right.

A truly effective pedagogy must take this into consideration. When dealing with a child who does not have its heart in the right place, speaking strictly anatomically, this must be taken into account; otherwise, it can have awkward consequences for the youngster. Because man is not just a physical apparatus, he does not necessarily have to be educated in such a way that abnormalities like this have to become an obstacle. Taking such aspects into consideration is what truly makes pedagogy an art.

A Professor Benedikt has examined the brains of many criminals. In Austria this was frowned upon because the people there are Catholics and they see to it that such things are not done. Benedikt was a professor in Vienna. He got in touch with officials in Hungary, where at one time there were more Calvinists, and he was given permission to transport the heads of executed criminals to Vienna. Several things then happened to him. There was a really ruthless killer who had I don't know how many murders on his conscience and who also had religious faith. He was a devout Catholic. When a rumour broke out that the brains of criminals were being sent to Professor Benedikt in Vienna, this criminal who was a cold-blooded murderer protested. He did not want his head sent to the professor because he didn't know where he would look for it to piece it together with the rest of his body when the dead arise on Judgment Day. Even though he was a hardened criminal, he did believe in Judgment Day.

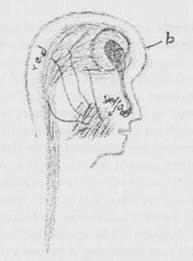

So what did Professor Benedikt find in the brains of criminals? In the back of our heads we have a “little brain,” the cerebellum, which I shall speak about later on. It is covered by a lobe of the “large brain,” the cerebrum. It looks like a small tree (drawing). On top it is covered by the cerebrum and the occipital lobe. Now, Professor Benedikt discovered that in people who have never committed murder or a theft—and there are such people—the occipital lobe extends down to here (drawing), whereas in those who had been murderers or other criminals the lobe did not extend so far; it did not cover the cerebellum below.

A malformation like that is naturally congenital; a person is born with it. And, gentlemen, there are a great many people born with an occipital lobe that is too small to properly cover the cerebellum! It can be made up for by education, however. Nobody has to become a killer because he has a shorter occipital lobe; he becomes a criminal only if he is not properly educated. From this you can see that if the body is not correctly developed one can compensate for it with the forces of the soul. Therefore, it is nonsense to say that a person cannot help becoming a criminal—which is what the otherwise brilliant professor stated—because as an embryo he was incorrectly positioned in the mother's womb and thus did not properly develop the occipital lobe. He might be quite well-educated by accepted standards, but he is not properly educated in regard to such an abnormality. Of course, he cannot help the inadequacies of education, but society can help it; society must see to it that the matter is handled correctly in education. I mention this so you may realize the great significance of the whole organization of man.

Let us return again to the subject of the dog. We must admit that in the dog the nose is especially well-developed. Now, gentlemen, what do we actually smell? What does a dog really smell? If you take a bit of substance like this piece of chalk, you will not smell it. You will be able to smell it only if the substance is set on fire, and the ingredients evaporate to be received into the nose as vapor. You cannot even smell liquid substances unless they first evaporate. We smell only what has first evaporated. Also, there must be air around us with which the vapours from substances can mix. Only when substances have become vaporous can we smell them; we cannot smell anything else. Of course, we do smell an apple or a lily, but it is nonsense to say that we smell the solid lily. We smell the fragrance arising from the lily. When the vapor-like scent of the lily wafts in our direction, then the nerve in the nose is able to experience it.

What a primitive tribesman smells of his enemy are his evaporations. You can conclude from this that a man's presence makes itself felt much farther than his hands can reach. If we were primitive people and one of us were down in Arlesheim, he would know if an adversary of his were up here among us. This would mean that his foe would have to make his being felt all the way down to Arlesheim! (Arlesheim is about 154 miles from Dornach.) Indeed, all of you extend to Arlesheim by virtue of what you evaporate. On account of a man's perspirations, something of himself extends a good distance around himself, and through that he is present to a greater degree than through what one can see externally.

Now, the dog does something interesting that man cannot do. All of you are quite familiar with it. If somewhere you meet a dog you know well and that is equally well-acquainted with you, the animal will wag its tail because it is glad to see you. Yes, gentlemen, why does it wag its tail? Because it experiences joy? A man cannot wag his tail when he is happy, because he does not have one anymore. In this regard man has become stunted, insofar as he has no way to immediately lend expression to his joy. The dog, however, smells the person and wags its tail. On account of the scent, the dog's whole body reaches a state of excitement that is expressed by the tail muscles receiving the experience of gladness. In this respect man has reached the stage where he lacks such an organ with which he could express his joy in this way.

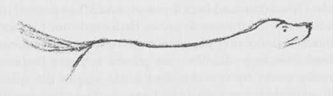

We see that while man is more cultivated than dogs, he lacks the ability to drive the sensation of smell down his spinal cord. The dog can do this; the scent enters its nose and is transmitted down the spinal cord, and then the dog wags its tail. What enters its nose as scent travels down the spinal cord. The end of the spine is the tail, and so it wags it. Man cannot do that and I shall tell you why he cannot. Man also possesses a spinal cord, but he cannot transmit a scent through it. Now, I shall draw the whole head of the human being in profile (diagram). The spinal cord continues down on the left. In the case of the dog it becomes the tail, which the animal can wag. Man, however, turns the force of his spinal cord in the other direction. Indeed, he has the capacity to change many things around, something that the animals cannot do. Thus, animals walk on all fours, or if they do not, as in the case of some monkeys, it is all the worse for them. They are actually organized to walk on all fours. But the human being raises himself up. At first man too walks on all fours, but then he stands erect. The force through which he accomplishes this and that passes through the spinal cord is the same force that pushes the whole brain forward. It is actually quite interesting to see a dog wag its tail. If a human being compared himself to the dog, he can exclaim, “Isn't that something; it can wag its tail, and I cannot!”

The whole force that is contained in this wagging tail, however, has been dammed back by man, and it has pushed the brain forward. In the dog it grows backward, not forward. The force that the dog possesses in its tail we turn around and lead into the brain. You can picture to yourselves how this really works by realizing that at the end of the spine, where we have the so-called tail bone, is the coccyx, which consists of several atrophied vertebrae. In the dog they are well-formed and developed; in us they are a fused and completely stunted protrusion that we can no longer wag. It ends here and is covered by skin. Now, we are able to turn this whole “wagging ability” around, and if in fact the top of the skull were not up here (b), upon smelling a pleasant odour we could wag with our brain, as it were. If our skull bones did not hold it together, we would actually wag with our brain toward the front when we are glad to see somebody.

You see, this is what marks the human organization; it reverses that function found in the animals. This tail wagging ability is still developed but it is reversed. In reality, we too wag something, and some people have a sensitivity for perceiving it. Isn't it true that court officials fawn and cringe in the royal presence? Of course, theirs is not a wagging like that of a dog, but some people still get the feeling that they are really wagging their tails. This is because their wagging is on the soul level and indeed looks like tail wagging. If one has acquired clairvoyance—something that is easily misunderstood but that merely consists of being able to see some things better than others—then, gentlemen, one does not just have the feeling that a courtier is wagging his tail in front of a personage of high rank; one actually sees it. He does not wag something in the back, but he does indeed wag something in the front. Of course, the solid substances within the brain are held together by the skull bones, but what is developed there in the form of delicate substantiality, as warmth, wags when a courtier is standing before royalty. It fluctuates. Now it is warm, now a little cooler, warmer, cooler. Someone with a delicate sensitivity for this fluctuating warmth, who is standing in the presence of courtiers surrounding the Lords, sees something that looks like a fool's cap wagging back and forth in front. It is correct to say that the etheric body, the more delicate organization of man, is wagging in front. It is absolutely true that the etheric body wags.

In the dog or the elephant all this is utilized to form the spinal cord. What remains stunted in both these animals is reversed and pushed forward in man. How is that? In the brain two things meet: The “wagging organ,” which has been pushed forward and is present only in man, and the olfactory nerve, which is also present in man. In the case of the dog, the olfactory nerve enlarges considerably because nothing counteracts it; what would restrain it is wagging in the back. The human being turns this around. The whole “wagging force” comes forward to the nose, and thus the olfactory nerve is made as small as possible; as it penetrates into the brain it is compressed from all sides by what comes to meet it there. You see, man has within the head an organ that, on the one hand, forces back his faculty of smell but, on the other, makes him into a human being. This organ results from the forces that are pushed up and forward.

In the case of the dog and the elephant, much of the olfactory nerve is located in the forward part of the brain; a large olfactory nerve is present there. In man, this nerve is somewhat stunted. The nerves that were pushed upward from below spread out instead. As a result, in this spot where in the dog sensations of smell spread out much further, in the human being the noblest part of the brain is located. There, located in the forward part of the brain, is the sense for compassion, the sense for understanding other human beings, and that is something noble. What the dog expends in its tail wagging, man transforms into something noble. There, in the forward part of the brain, just at the spot where the lowly nose would otherwise transmit its olfactory nerve, man possesses an extraordinarily noble organ.

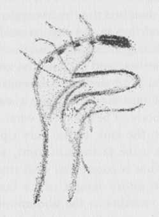

I have mentioned that we do not smell equally well with the left and the right nostrils. Now, try to recall someone who is in the habit of making pronounced gestures. What does he do when he is pondering something? I am sure you have seen it. He reaches up with his finger or his hand and touches his nose; his index finger comes to rest directly over the septum, the inner wall dividing the nasal passages. For right here, behind the nose and within the brain, the capacity for discrimination has its physical expression.

The septum of the dog enables it not only to follow a lead exactingly but also to distinguish carefully with the left and the right nostrils how the scents appear to either one or the other. The dog always has in its right nostril the scent of what it is pursuing at the moment, while in the left it has the scents of everything it has already pursued. The dog therefore becomes increasingly skilful in pursuit, just as we men become more and more intelligent when we learn more and commit facts to our memory. The dog has a particularly good memory for scents, and that is why he becomes such a keen tracker.

A trace of that still exists in human life. Man's sense of smell has become dulled, but Mozart, for example, was sometimes inspired with his best melodies when he smelled a flower in a garden. When he pondered the reason for this, he realized that it happened because he had already smelled this flower somewhere else and that he had especially liked it. Mozart would never have gone so far as to say, “Well, I was once in this beautiful garden in such and such a place, and there was this flower with a wonderful fragrance that pleased me immensely; now, here is the fragrance again, and it makes me almost want to, well—wag my tail.” Mozart would not have said that, but a beautiful melody entered his mind when he smelled this flower the second time. You can tell from this how closely linked are the senses of smell and memory.

This is caused not by what we human beings absorb as scents but rather by what we push forward in the brain and against it. Our power of discrimination is developed there. If a person can think especially logically, if he has the proper thought relationships, then we can say that he has pushed his brain forward against his olfactory nerve, that he has actually adjusted the brain to what otherwise would have also been the olfactory nerve. We can say, too, that the more intelligent a man is, the more he has overcome the dog nature in himself. If a person were born with a dog-like capability to smell especially well, and he was educated to learn to distinguish things other than smells, he would become an unusually clever person because he would be able to discriminate among these other things by virtue of what he had pushed up against the olfactory nerve.

Cleverness, the power of discrimination, is basically the result of man's overcoming his sense of smell. The elephant and the dog have their intelligence in their noses; in other words, it is quite outside themselves. Man has this cleverness inside himself, and that is what distinguishes him. Hence it is not enough just to check and see whether the human being possesses the same organs as the animals. Certainly, both dog and man have a nose, but what matters is how each nose is organized. You can see from this that something is at work in man that is not active in the dog, and if you perceive this you gradually work yourself up from the physical level to the soul level. In the dog the nose and the bushy end of the spine, which is only covered by skin permeated with bony matter, have no inclination to grow toward each other. This tendency originates only from the soul, which the dog does not have in the way a man does. So, then, I have described the nose and everything that belongs to it in such a way that you see its continuation into the brain and find that man's intelligence is connected with this organ.

There is another sense that is quite similar to the sense of smell but in other respects totally different: the sense of taste. It is so closely related that the people in the region where I was born never say “smell”; the word is not used there at all. They say instead, “It tastes good,” or “It tastes bad,” when they smell something. Where I was born they do not talk of smelling but only of tasting. (Someone in the audience calls out, “Here, too, in Switzerland!”) Yes, also here in Switzerland you don't talk of smelling; smelling and tasting appear so closely related to people that they don't distinguish between the two.

If we now investigate the sense of taste, we will find that here there is something strange. Again, it is somewhat like it was with the sense of smell. So, if you take the cavity of the mouth, here in the back is the so-called soft palate, in the front is the hard palate, and there are the teeth with the gums. If you examine all this you will find something strange. Just as a nerve runs down into the nose, so here, too, nerves run from the brain down into the mouth. But these nerves do not penetrate into the gums, nor do they extend into the hard palate in front. They reach only into the soft palate in the back, and they go only into the back part of the tongue, not its front part. So if you see how the nerves are distributed that lead to the sense of taste, you will find only a few in front, practically none. The tip of the tongue is not really an organ of taste but rather one of touch. Only the back part of the tongue and the soft palate can taste. The mouth is soft in the back and hard in the front; only the soft parts are capable of tasting. The gums also have no sensation of taste.

The peculiar thing is that these nerves that convey the sense of taste in man are also connected primarily with everything that makes up the intestinal organization. It is indeed true that first and foremost a food must taste good, although its chemical composition is also important. In his taste man has a regulator for the intake of his food. We should study much more carefully what a small child likes or does not like rather than examine the chemical ingredients of its food. If the child always rejects a food, we shall find that something is amiss with its lower abdominal organs, and then one must intervene there.

I have already sketched the “tail wagging ability” that is reversed in man and that in the dog extends all the way into the back. If we now move forward from the tail, we reach the abdomen, the intestines, and to these the taste nerves correspond. It is like this: When a dog abandons itself to smelling, it wags its tail, which signifies that it drives everything through its entire body. The effects of what it smells pass all the way through to the end, to the very tip end of the tail. The tip of the nose is the farthest in front, and the tail is the farthest behind. What is connected with smelling in the dog passes through the entire length of its body, but what it tastes does not; it remains in the abdominal area and does not go as far. We can see from this that the farther something related with the nerves is located within the organism, the less far-reaching is its effect in the body. This will teach us to understand even better than we know already that the whole form of man depends on his nerves. Man is formed after his nerves. In the case of the dog, its tail is formed after the nose. What are its intestines formed after? They are formed after the nerves of the muzzle. The nerves are situated on one end, and they bring about the form on the other end. This is something that you must take as a basis for further consideration. You will gain much from realizing that the dog owes its whole tail wagging ability to its nose, and that when it feels good in the abdominal area, this is due to the nerves of the mouth. We shall learn more about this later.

It is extraordinarily interesting how the nerves are related to form. This is why I said the other day that even a blind person benefits from his eyes; even though the eyes are useless for sight, their nerves still help shape the body. The way a person appears is caused by the nerves of his head and in part by the nerves of his eyes, as well as by many other nerves. Therefore, if we want to understand why the human being differs in form from the dog, we have to think of the nose! The nose plays an important part in the shape of a dog, but in the human being it is overcome and somewhat subdued in its functions. In the dog, the nose occupies a higher rung on the ladder; it is the head-master, so to speak. In man, the function of the nose is forced back. The eye and the ear are certainly more important for his formation than is the nose.